Andrei Bîrsan: Anii 80 / The 80s

ENGLISH

Andrei Bîrsan is one of the few Romanian photographers with an archive an images from the 1980s, when he was a teenager / young adult. I chatted with him about his passion for photography, the fear of being branded an ‘enemy of the people’ and about misinterpreted nostalgia.

ROMÂNĂ

Andrei Bîrsan este unul din puținii fotografi români cu o arhivă de imagini din anii 80, pe vremea când era adolescent / tânăr. Am stat de vorbă despre pasiunea lui pentru fotografie, despre frica de a nu fi etichetat drept dușman al poporului și despre nostalgia greșit interpretată.

AV: Where were you living in the 80s?

AB: At Dristor. On Ion Șulea boulevard. Which at some point was called Josip Broz Tito. Now it’s Camil Ressu. I spent much of my childhood at my grandmother’s, on Calea Moșilor. It was a very nice neighbourhood, I liked it and was very fond of it. We had the Foișorul de Foc (Fire Tower), where lots of fire engines were parked in front of. We used to climb over them. That was my childhood. And in relation to photography, in the autumn of ’79 - I was in the 8th grade then - my father gifted me a book called ‘My Passion, Photography’. A little book in the Caleidoscop collection. And then my mother gifted me a Russian camera, a Smena Symbol, for Christmas.

AV: Yes, the Smena. I know them. Whoever had a camera back then, had a Smena!

AB: Exactly! So that’s how my passion started. It’s interesting that they let me –for the half year or so I had left in secondary school, then college, then university, I took photos without any problems, in the classroom. Because I think they probably didn’t take me seriously, they thought – he’s just a child with a Smena, nothing’s going to come out. But happily, they came out all right.

AV: Unde locuiai în anii 80?

AB: La Dristor. Pe bulevardul Ion Șulea. Care la un moment dat s-a numit Josip Broz Tito. Acum se numește Camil Ressu. Am copilărit la bunică-mea, pe Calea Moșilor, acolo era un cartier foarte interesant și mi-a plăcut foarte mult, țineam mult la el. Era Foișorul de Foc, erau mașini de pompieri în fața muzeului, și noi ne cățăram pe ele, asta era copilăria. Și cu fotografia, pur și simplu, în ‘79 in clasa a 8-a in toamna tata mi-a făcut cadou o carte, se numea Pasiunea mea Fotografia. O cărticică mică, în colecția Caleidoscop. Și de acolo a început totul. Aveam niște negative. Mi-am cumpărat substanțe, le făceam în hol. După aceea mama mi-a făcut cadou de Crăciun un aparat foto rusesc, Smena Symbol.

AV: Da, Smena. Le știu. Cine avea aparat foto, avea Smena!

AB: Exact! Deci, așa a început pasiunea. Interesant este că m-au lăsat, deci cât am mai apucat eu acolo în școala generală, juma de an, și după la liceu și în facultate am făcut fotografii fără să am probleme, în clasă. Pentru că, cred că nu mă luau în seamă, ziceau e aparat Smena, copil, eh, n-o să iasă nimica. Dar din fericire au ieșit.

AV: Were there photography clubs in schools?

AB: Yes, there were. And I regret I never took part. There were photography clubs and there was an artistic association of photographers in Romania as well. I regret not taking part, because I think maybe technically speaking, I would’ve been better. But as someone once told me, maybe if my technique was better my ideas could’ve been spoiled.

AV: Right.

AB: But if we look at what’s left from the Association of Photography Artists in Romania, there’s nothing! Smoke! There were thousands of people there, and nothing remains. I have no idea what they were doing, I don’t know, maybe just shooting flowers or stones, who knows? That’s what I think is interesting, that photographs that matter from that period were produced by non-photographers, who’d never been in associations and so on. Engineers, architects.

AV: Like Andrei Pandele, right?

AB: Yes, exactly. Architect – he also took photos. Or Dan Dinescu, although he was also a photographer. But I am talking about the majority – including myself. I was an engineer. Dan Vartanian or Șerban Lăcrițeanu, also engineers.

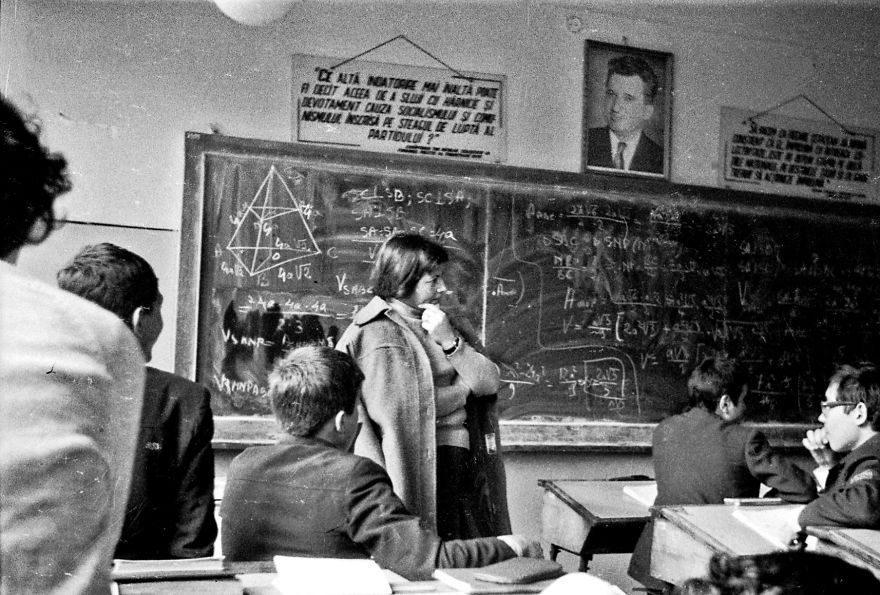

AV: So many of your photos were taken at your school, in your classroom – I see many that get shared on social media, not always crediting you unfortunately. Like the one with the portrait of Ceaușescu above the blackboard.

AB: Yes, that’s also on the book cover of The 80s.

AV: Or the teacher with her winter coat on.

AB: Haha, yes, and the one with the shovel! With a luxury winter coat on! Yeah, those were the times!

AV: Erau cluburi de fotografie la școală?

AB: Erau cluburi. Asta îmi pare rău că n-am participat și la un club. Erau cluburi de fotografie, exista și o asociație artistică a fotografilor din România. Și îmi pare rău că n-am participat, pentru că poate, tehnic vorbind, aș fi fost mult mai bun. Deși cineva îmi spunea ca poate dacă tehnica era mai buna îmi strica ideile.

AV: Exact.

AB: Că dacă ne uităm acum după Asociația artiștilor fotografi din România n-a mai rămas nimic. Fum! Erau mii de oameni acolo, n-a rămas nimic. Nu știu ce făceau ei acolo numai floricele, nu știu, pietre, știi? Asta e interesant, că fotografia din acea perioadă care contează s-a produs de oameni care nu sunt fotografi. Care n-au fost în asociații sau mai știu eu ce. Ingineri, arhitecți.

AV: Da, cum a fost și Andrei Pandele, nu?

AB: Exact. Arhitect, a făcut poze. Sau Dan Dinescu, deși era și fotograf. Dar zic așa de cei mai mulți, cum am fost eu. Eu eram inginer. Sau Dan Vartanian, inginer, sau Șerban Lăcrițeanu, inginer.

AV: Deci în școală, în clasă practic, ai făcut multe fotografii – știu câteva care au fost publicate, și circula multe pe social media care din păcate nu iți atribuie prea des dreptul de autor! Cum ar fi aceea cu portretul lui Ceaușescu deasupra tablei.

AB: Da, care e și pe coperta albumului.

AV: Sau cu profesoara cu haina de iarna pe ea.

AB: Haha, da, da, și la lopată! Haina de lux de iarna! Da... alea erau vremurile!

AV: When did you first become aware, for the first time, that it could be dangerous – I was reading an article where you were talking about trying to take photos at the People’s House.

AB: Right then actually! Yes, exactly at that time – and it motivated me to keep taking photos but at the same time I ended up hating and fearing that area. So, I don’t have any photos with the People’s House being built. It’s strange when I think about it. I think subconsciously I was left very scared.

AV: Yes, fear was instilled everywhere. We lived a double life, didn’t we? One thing at home and another in public, careful what you said or did.

AB: You can see in my book Trecut-au Anii (The Years Gone By) that on many occasions I would go out with my girlfriend Mihaela to take photos of the town. I pretended to photograph her. But in fact, I was taking photos of the city.

AV: Right!

AB: You can imagine how awful it was – these times when you didn’t realise that out of nowhere, literally out of nowhere you could get into trouble. Just for taking photos in a random place where there was no sign to prohibit it. They could’ve stopped me from going to university, I could’ve become an ‘enemy of the people’. Yes, that’s how it was.

AV: I read about when your camera was confiscated.

AB: Twice I’ve had it confiscated. By some vigilant comrades. And sadly, even today there are many who would like to do that, to see this happen.

AV: Yes, there are. Just the other day I got shouted at by some security guy on the metro. I was taking photos for my project in the neighbourhood where I grew up.

AB: There’s lots of people who feel better, somehow superior if they can forbid something. For no other reason.

AV: Just like in communist times, the little people in positions of relative power over us like security guards or shop assistants!

AB: Exactly!

AV: Când ai conștientizat prima data că este, ca poate sa fie periculos – ți-am citit un articol despre când făceai poze în zona Casei Poporului de pildă.

AB: Chiar atunci! Chiar atunci da, și vezi asta m-a mobilizat sa fac poze în continuare dar în același timp m-a făcut să urăsc, să îmi fie teamă de zona aia. Deci eu n-am nici o poză cu Casa Poporului în construcție. Asta e ciudat, acum mă gândesc. Cred că în subconștient, am rămas cu o teamă.

AV: Da, și teama era infiltrată peste tot. Aveam o viață dubla, practic una făceai si vorbeai acasă si alta aveai voie să spui.

AB: Poți sa vezi in cartea Trecut-au Anii. De multe ori mergeam cu Mihaela, iubita mea, să facem poze orașului. Mă făceam că o pozez pe ea. De fapt pozam orașul.

AV: Așa, exact.

AB: Îți dai seama ce groaznic era – niște perioade în care nu-ți dădeai seama că din nimic, adică din nimic, puteai să ai mari probleme. Făceam fotografie într-un loc unde nu era nici un indicator de interzis, nimic, dar puteam sănu mai fac facultate. Să fiu clasat drept dușman al poporului. Da, și uite așa era.

AV: Am citit despre când ti-a fost aparatul foto confiscat.

AB: Da, de doua ori mi-a fost confiscat. De tovarăși vigilenți. Si din păcate și acuma sunt mulți care ar vrea să facă așa, să introducă asta.

AV: Da, sunt. Doar acum câteva zile a strigat la mine un paznic de la metrou când făceam niște poze pentru proiect în cartierul în care am copilărit.

AB: Da, sunt mulți care parca se simt ei mai bine așa, mai sus, daca interzic ceva. Nu de alta, știi?

AV: cum era și pe vremea comuniștilor, oameni mici în poziții de putere asupra noastră, paznici sau vânzătoare la magazine.

AB: Exact!

AV: After ‘89, when you started to show these photos from the ‘80s, how where they received? What reactions did you get?

AB: Basically, I ignored these photos for about 17 years. In 2007 when I created the association Bucurestiul meu Drag (My beloved Bucharest) they’d been in a box under my mother’s bed! I don’t even know if I still have everything I shot back then.

AV: Were they all developed?

AB: They were, and some enlarged. All the negatives were under my mother’s bed. She could’ve thrown them away. She probably did throw some away, to be fair. I wasn’t aware of what I had back then. It’s just when I started the association then I wanted to see what the city looked like before. And that’s how my archive was formed – or rather re-evaluated. With this association I reinvented myself, or I discovered myself.

AV: How do you relate to these images over time, now? Because I think if we look at photos at different ages and from different perspectives, they change their value, their content.

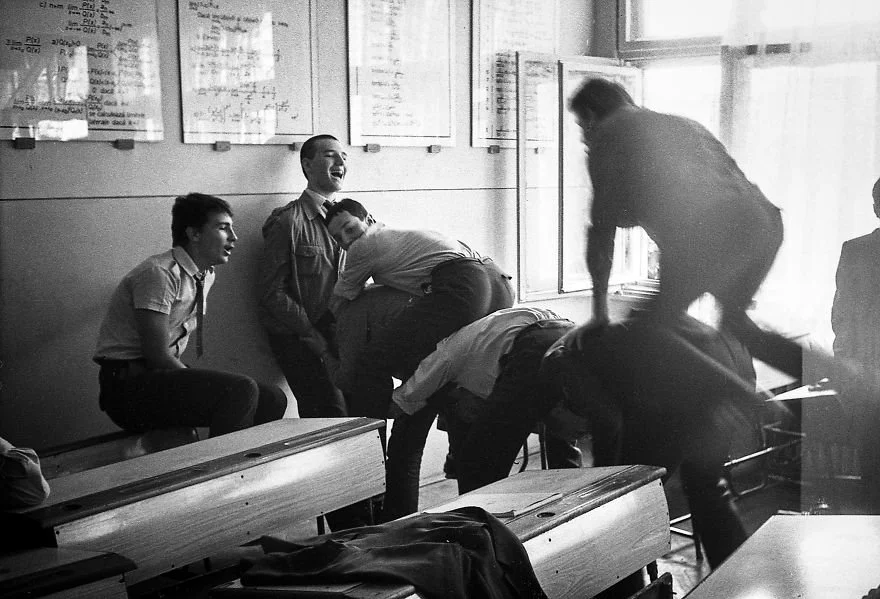

AB: That’s right. If you look at my photos from back then, you’ll see that what I captured, what I photographed, was nothing in particular – just everyday life. Little things. It wasn’t anything else. Fellow children in the classroom, at school, on the street. They weren’t artistic photographs like ‘fine art’ or whatever they’re called these days, or any rigorous documentation. We were simply 8th grade pupils, or college students. We had other preoccupations but among them, you see, I also took photographs. It just happened, it was a happy occurrence for me and those who enjoy seeing them.

AV: When was the first book published, or the first exhibition, and how were they received?

AB: The 80s at the Museum of Bucharest, that was the first one, they really liked it. Many in the audience found themselves in the photos, especially the classroom ones. How we played Capra (the Goat) or Lapte Gros (Thick Milk) or we talked to each other in class instead of paying attention. Many could relate. I think there should be so many more photos, from everyone who had cameras at the time, but maybe they got lost. Our museums should have a campaign to gather photographs. Of course, there are archives like Agerpres where you will find many images.

AV: Well, yes, but what I find extraordinary is that you captured, as you say, snippets of everyday life, because I think that’s what’s missing. I have vivid memories of my school days – for example, I don’t know if you had this, but there was this obsession one year with raising silkworms.

AB: We had to collect chestnuts, there were lots of chestnut trees in my neighbourhood in Titan. They even gave us some special towers to climb and reach the trees. But, interesting – silkworms!

AV: It was only one year and probably after your generation. And practically there isn’t a single photograph – at least not that I’ve found yet – that shows this phenomenon. Our entire sports hall at school was turned into a silkworm creche.

AB: Here, in Bucharest?

AV: Yes – I was in Grivița, School 173.

AB: We used to go and pick potatoes – I have a few photos from college or university – picking and sorting potatoes.

AV: Where did you go to University?

AB: TCM part of the Polytechnic, in Bucharest. I don’t have many photos from there. I remember I used to walk from the metro in Grozăvești, and there was a factory nearby, Semănătoarea. And there was a field in front of it, full of combine harvesters! I think they gathered them there and then, at a certain time of the year, before harvest, they sent them into the country.

AV: Interesting! What an image!

AB: Yes, it would’ve made a very interesting photo, but I didn’t get it!

AV: După ‘89, când ai început sa scoți fotografiile astea din anii 80, cum au fost primite? Care au fost reacțiile?

AB: Practic fotografiile astea le-am ignorat, vreo 17 ani, până în 2007, când am făcut o asociație Bucureștiul meu Drag. Ele stăteau la mama sub pat, într-o cutie.

Nici nu știu dacă mai sunt toate pe care le-am făcut eu în acea perioadă.

AV: Și erau toate developate?

AB: Erau developate, unele mărite. Toate negativele erau sub pat la mama, putea să le arunce. Cred că a și aruncat o parte din ele, să spun drept. Nu, atunci nu eram conștient de ele. Dar când am făcut asociația am zis, hai sa vedem cum era înainte orașul. Si așa a apărut arhiva mea, să zic – am reevaluat-o și de fapt cu asociația asta m-am reinventat pe mine sau m-am descoperit pe mine.

AV: Chiar asta voiam să te întreb: cum te raportezi la fotografiile astea, în timp? Pentru că mie mi se pare că uitându-ne la ele la alta vârstă si din alta perspectiva își schimba valoarea, conținutul.

AB: Exact, și dacă te uiți la ele o să observi că eu am fotografiat pe vremea aceea nimicul, pur și simplu viața de zi cu zi. Lucrurile mărunte. N-a fost nimic altceva. Copiii în clasă, la școală, pe stradă, deci nu erau fotografii artistice, cum zic ăștia acuma fine art, sau nu era o documentare din asta riguroasă. Pur și simplu, eram elevi în clasa a 8-a, sau la liceu. Aveam alte treburi, dar printre, uite, făceam și fotografii din astea. Deci pur și simplu a fost o întâmplare, pentru toată lumea, și pentru mine și pentru cei care se bucură de ele.

AV: Și ce fel de reacții ai avut când a fost prima expoziție sau prima carte publicată?

AB: Asta a fost o cu anii 80 la muzeul Bucureștiului, le-a plăcut foarte mult. S-au regăsit mulți, mai ales in pozele astea din clasa. Cum jucau capra sau lapte gros sau vorbeau unii cu alții la ore in loc sa lucreze, sa fie atenți. S-au regăsit foarte mulți acolo. Da, vezi, ar trebui să fie mult mai multe poze, de la toată lumea care mai avea aparate, dar poate s-au pierdut foarte multe. Muzeele noastre ar trebui sa aibă o campanie de strâns fotografii. Bineînțeles ca există de exemplu la Agerpres, o sa găsești exista foarte multe.

AV: Da, dar mie mi se pare extraordinar că tu ai păstrat exact cum zici tu din viața de zi cu zi, pentru că asta cred că lipsește. Am amintiri foarte vii în minte despre ce făceam ca elevi. Nu știu daca voi făceați la scoală, noi aveam într-un an obsesia să creștem viermi de mătase.

AB: Da noi culegeam castane, erau castani pe drum, aici, în cartier, în Titan. Da, și primeam chiar niște turnuri speciale pe care ne urcăm ca să ajungem la copaci. Dar, interesant – viermi de mătase!

AV: A fost într-un singur an, probabil după generația ta. Da, și practic nu există, sau nu am găsit pană acum, vreo poză care să arate acest fenomen – practic nouă ne-au transformat toată sala de sport într-o crescătorie de viermi de mătase.

AB: Aici, in București?

AV: Da, da – eram în Grivița, la Școala 173.

AB: Noi mergeam la cartofi, de multe ori – am poze din liceu, de la facultate, la cules si sortat de cartofi.

AV: Si facultatea unde ai făcut-o?

AB: TCM in București. Dar vezi de acolo nu am poze. Țin minte ca ieșeam acolo la metrou, la Grozăvești. Și alături era fabrica Semănătoarea. Era un câmp acolo, plin de combine! Cred că le strângeau acolo și la o anumită perioadă din an, înainte de seceriș le trimiteau în țară.

AV: Interesant! Ce imagine!

AB: Da ar fi fost interesanta o fotografie cu asta, dar n-am!

AV: What do you think about the current trend of nostalgia after communist times? All these people saying it was better back then?

AB: It’s entirely toxic. Absolutely toxic. It was better to be young! You know, like that joke with the two old men, one says: it was better in Ceaușescu’s times, and the other one asks why? Because I could still get it up then! That’s how that is. That’s the level, honestly that’s the level – you can’t be nostalgic after those times, no matter what. You’re nostalgic after your youth, not…

AV: Not the living conditions!

AB: Yes, and the thing is we were young back then and – at least in my case – we had our own bubble, my parents for example never sent me to any queues. I don’t know where they bought stuff, they queued up for it, or the black market, I don’t know. But they kept us in our own bubble, otherwise it was terrible.

AV: That’s right – the same with my generation, we were about 14 at the Revolution. We were protected by family, as children.

AB: Humiliating times. Absolutely humiliating. Think about people bragging about buying something that was refused for export! That was something supreme! You had a TV that was refused for export, that was the utmost! Much better than what was being produced for the home market.

AV: I remember – it was a thing to be proud of, being able to buy something that was refused for export.

AB: So that’s what I’m saying, nostalgia is misunderstood. They don’t think.

AV: This is one of the reasons I started this project. To help preserve the documentation of everyday life back then.

AB: Our parents gave us the chance to have some fun as kids, only thanks to them. I remember my dad leaning over the radio listening to Radio Free Europe. They were talking about politics in the house, but not too much. No, those were times against nature. Which, unfortunately, ruined many people.

AV: Ce părere ai despre curentul asta de nostalgie după vremurile comuniste, deci toată lumea care zice că era mai bine atunci?

AB: E total toxic. Absolut toxic. Era mai bine că erai tânăr, știi cum era bancul ăla cu niște moși cum ziceau era mai bine pe vremea lu’ Ceașca, păi de ce? Pai mi se mai scula și mie. Știi? Cam așa! Ăsta e nivelul, pe bune, ăsta-i nivelul, n-ai cum să ai nostalgia acelor vremuri, nu ai cum, oricât ai vrea. Adică, vine nostalgia după faptul ca erai tânăr, nu...

AV: Exact, după vârstă, nu după condițiile de trai.

AB: Da, și noi ca tineri pe vremea aia, și eu personal, și mai dihai, noi am avut o bula a noastră - părinții mei, cel puțin, nu m-au trimis la cozi niciodată. Nu știu de unde cumpărau, stăteau ei la coadă, cumpărau de la bișniță, nu știu. Si asta zic, noi aveam bula noastră, că altfel era groaznic.

AV: Absolut. Și așa e, pentru generația mea de pilda, eu aveam 14 ani la revoluție, am fost mai protejați, că eram copii.

AB: Umilitor, absolut umilitor. Gândește-te cum se lăudau unii și alții, că au cumpărat ceva refuzat la export! Asta era ceva suprem. Adică aveai un televizor refuzat la export, era mai bun decât ce se producea in Romania pentru noi, era suprem.

AV: Da, țin minte, era de mândrie să ai ceva refuzat la export.

AB: Deci asta zic, nostalgia e prost înțeleasă și nu gândesc.

AV: Da, practic și de-asta m-am apucat de proiectul ăsta, ca să se păstreze documentarea vieții reale de zi cu zi.

AB: Noi aveam șansa să ne distrăm când eram mici, dar asta numai si numai datorită părinților. Țin minte pe taică-meu mereu aplecat peste radio ascultând Europa Liberă și alte chestii - mai vorbeau ei în casă despre politică, dar nu prea mult. Nu, au fost niște vremuri contra naturii. Care, din păcate, i-au stricat pe mulți.

AV: Tell me, what do you remember from the Revolution? Where were you back then?

AB: I was living somewhere on my own, no TV, no phone, nothing. So I found out by accident about the Revolution! I took my camera and went to the Palace Square and the Palace Hall, in the morning, and took some photos. There was still shooting going on then. Lots of smoke. That’s what I got from the Revolution. And then, well, I still came back later when it was over. People used to come out for a walk and to see the tanks.

AV: Si de la Revoluție, ce iți mai amintești, unde erai? Ce făceai?

AB: Pe vremea aia stăteam singur undeva fără telefon, fără televizor, fără nimic. Așa că întâmplător am aflat de Revoluție și m-am dus și eu cu aparatul foto. Am câteva poze la Revoluție, de dimineața, în Piața Palatului, la Sala Palatului. Încă se mai trăgea. Era fum. Cam astea sunt pozele mele in timpul revoluției. Că după a mai fost o plimbare când oamenii veneau să vadă tancurile.

All images on this blog post are courtesy of Andrei Bîrsan, all rights reserved (c) Andrei Bîrsan. You can see more of Andrei’s work on https://abujie.ro and https://www.boredpanda.com/how-was-my-life-of-a-child-teen-or-student-between-1979-1989-in-communist-romania