Andreea Chirică: The Year of the Pioneer

ENGLISH

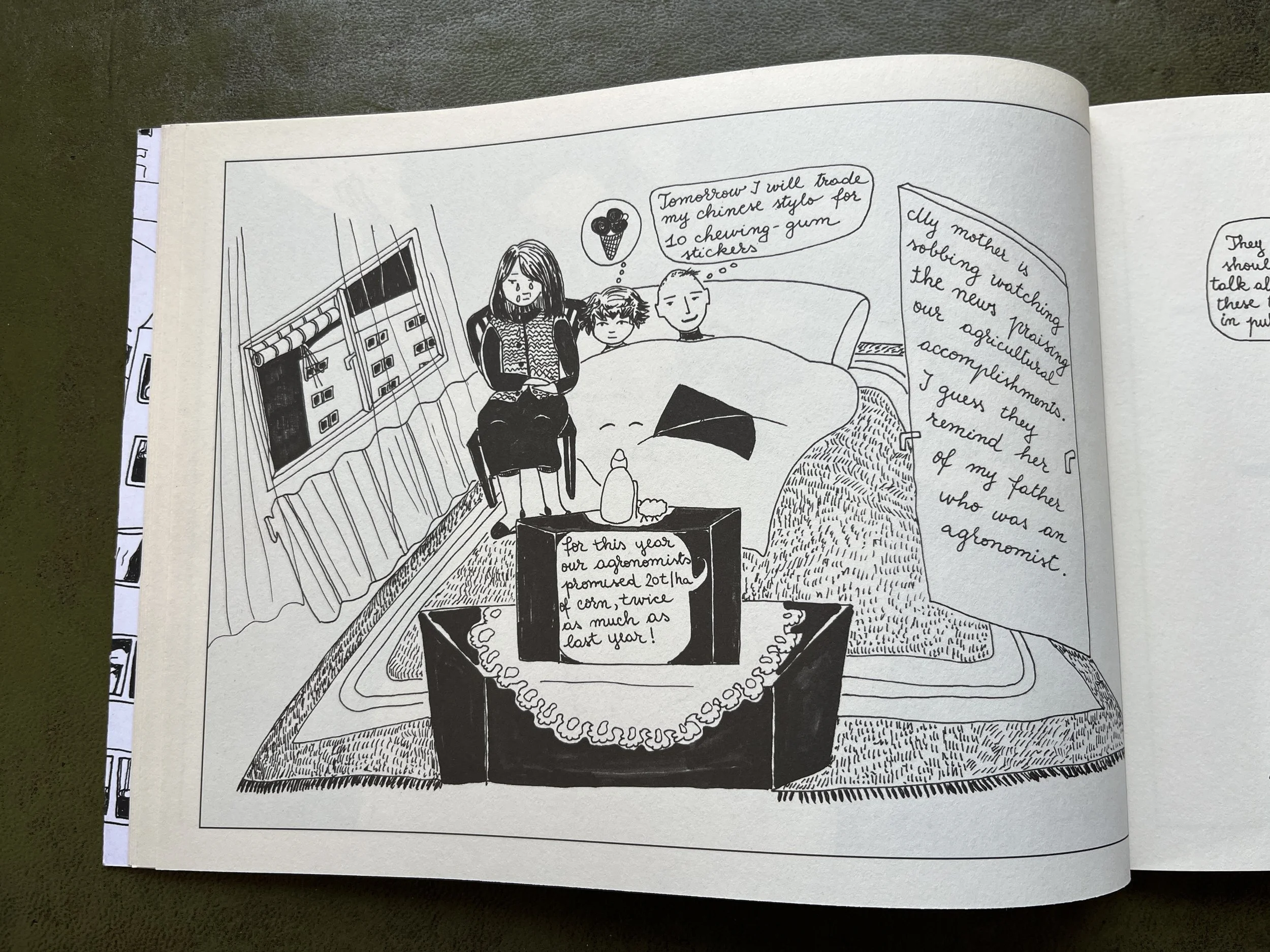

On a hot summer’s afternoon, I sat down to chat with Andreea Chirică. About her 2011 book The Year of the Pioneer. About the artistic act, about remembrance, inter-generational trauma, and about how we remember, as individuals and as a society, the terrible decade of the 1980s in Romania.

ROMÂNĂ

Într-o după amiază călduroasă de vară, am stat de vorbă cu Andreea Chirică. Despre cartea ei din 2011 The Year of the Pioneer. Despre actul artistic, despre aducere aminte, traume inter-generaționale, si despre cum ne amintim, ca indivizi și ca societate, de cruntul deceniu al anilor 1980 din Romania.

AV: Tell me about The Year of the Pioneer – how did you get the inspiration for it? How did you start to think about that time?

AC: I had a French boyfriend back then, and I used to tell him about my childhood. I liked to draw, so I started a blog. I used to post drawings, quite often – well, fairly rudimentary ones, I think. It’s how I wanted them, almost childish.

AV: Very apt otherwise, right? Since the book is told from a child’s point of view.

AC: Yes, that’s right. I used to feel free, just drawing for friends. I’d never got back to them since. After all these years, I think if I were to do it again, I’d censor myself more. I’d think more about the concept, the artistic project. The book doesn’t have a narrative thread. They’re just memories put together one after the other, but somehow focused around a single year, 1986.

AV: That was an important year for the 80s.

AC: Yes, there was the Chernobyl disaster, for one. I lived in Medgidia then, and we had the Cernavoda Nuclear Power Plant close-by. I think we panicked even more because of that. Same year, there was the European football championship where Steaua won.

AV: Yes! I love your illustration with ‘Duckadam apărăăăăăăă!’ (EN penalty save), I can almost hear the voice of the sports commentator on TV at the time!

AV: Spune-mi despre The Year of the Pioneer – cum ti-a venit inspirația? Cum ai început să te gândești la acea perioadă?

AC: Aveam un iubit francez și îi povesteam despre copilărie. Îmi plăcea să desenez și am început un blog. Postam des desene. Destul de rudimentare. Mă rog, am vrut eu să fie așa, mai copilărești.

AV: Foarte relevant de altfel, nu? Este o carte din perspectiva unui copil.

AC: Da, așa e. Atunci mă simțeam foarte liberă, desenam pentru prieteni. De atunci n-am mai revenit la ele. Acum, dacă aș face-o din nou după atâția ani, cred că m-aș cenzura mai mult și n-ar fi la fel. M-aș gândi eu mai mult la concept, la proiectul artistic. Cartea nu are un fir narativ. Sunt niște amintiri puse unele după altele, dar cumva concentrate într-un an, 1986.

AV: E un an destul de important pentru perioada anilor 80.

AC: Da, a fost dezastrul de la Cernobîl. Eu eram in Medgidia, și era centrala de la Cernavoda. Pentru noi cred ca s-a simțit mai tare panica. Tot in același an a fost campionatul european de fotbal.

AV: Da! E super ilustrația ta cu ‘Duckadam apărăăăăăăă!’ parca aud vocea comentatorului de la televizor!

AC: It was an interesting year; I remembered it well. Some things went under the umbrella of this year, although they may have happened a little before or after. But basically, these are all just childhood memories – without a narrative thread. They are some of the moments that marked me the most. Good ones and bad ones. They stuck with me, and they come and go in waves. The book is somewhat childish, funny and optimistic.

AV: How did others perceive it after publication?

AC: Some saw it through a nostalgic lens, although for me there was no nostalgia, politically speaking, no longing after that period. But it was my childhood after all. I am thinking that, had I produced this book after several years, after being through counselling and gaining a more nuanced outlook on my childhood, it would’ve been a different book. As it stands, the book appears naïve on the surface – I don’t get into family relationships or how we were raised and educated, and how that influenced the type of adults we became.

AV: And if you were to work on something similar now, how do you think it would be different?

AC: I think I’d do something about the relationship with my mum, you know? Like many other relationships of children with their mothers at that time – how they influenced us and had an impact on who we became. How they were raised, how we were raised, against the political and social background of the time. But I would go a bit deeper, beyond the surface – beyond the ‘postcard’ views of the communist times. I think I now feel the need for some more profound conversations about my childhood, especially in relation to things I don’t remember or can’t explain.

AV: I can relate. My biggest regret is that I never got to have these conversations with my mum. But I think about her all the time when I write, when I create – what would she say? Although it’s quite possible that she might never have wanted to talk much about it. Women were impacted differently.

AC: Yes, I’m also interested in this. How were they impacted? You know, we lived for so many years thinking there was this equality? This perceived equality between women and men. Women in the East worked and on paper they had equal rights with men, and we celebrated the 8thMarch (EN International Women’s Day) but in reality? What was happening deep down? How were couple relations? It’s an area that seems entirely unknown. At the time everything that was said was propaganda.

AC: A fost un an interesant, cred ca mi l-am amintit mai bine. Mă rog, unele lucruri le-am pus sub umbrela acestui an, deși poate s-au întâmplat puțin înainte sau după. Practic, sunt niște amintiri din copilărie. Nu urmeazăun fir narativ, sunt pur și simplu momentele care ne-au marcat mai mult. Fie bune, fie rele. Au rămas și vin așa, ca niște valuri. Cartea e cumva copilăroasă, ușor amuzantă, optimistă.

AV: Si alții cum au recepționat-o?

AC: După ce am publicat-o, a fost privită de către unii sub o notă nostalgică, deși pentru mine nu era nici o notănostalgică, politic vorbind, cu privire la perioada asta. Dar, na, era copilăria mea. Mă gândesc acum, dacă aș fi făcut-o după alți ani, după ce am făcut terapie și mi-am privit copilăria altfel, probabil ar fi ieșit altă carte. Așa pare naiva la suprafață, nu mă duc în relațiile mele cu familia, cum eram crescuți, educați si cum am ajuns ca adulți.

AV: Și dacă ai mai lucra acum la ceva similar, cum crezi că ar fi diferit?

AC: Cred că aș face ceva despre relația mea cu mama. Știi? Ca relațiile multor copii din perioada aia cu mamele lor. Cum ne-au influențat și cum și unde am ajuns. Cum au fost crescute ele, cum am fost crescute noi, bineînțeles, pe fondul politic și social de atunci. Dar cumva m-aș duce mai la interior. Nu așa, gen vederi din perioada comunistă. Cred ca simt nevoia unor discuții mai profunde legate de copilăria mea, apropos de lucruri pe care nu mi le amintesc sau nu mi le explic.

AV: Înțeleg perfect. Cel mai mare regret al meu e ca nu am apucat sa am aceste conversații cu mama. Dar măgândesc la ea tot timpul când scriu, ce ar zice ea? Deși e posibil sa nu fi vrut sa vorbească prea mult. Femeile au fost marcate diferit.

AC: Da,și pe mine măintereseazăasta. Cum a fost marcate ele.Știi căam trăit mulți ani cu gândul căexistăaceastăegalitate? Cumva de formă, între femeiși bărbați. Cătoate femeile în Est munceauși aveau teoretic drepturi pe hârtie egale. Sărbătoream 8 martie ziua femeii dar de fapt ce se întâmpla în interior? Cum erau relațiile de cuplu? Mi se pare o zona complet necunoscuta. În perioada aia tot ce s-a scris era propagandă.

AV: Where did you publish? And where was the book distributed?

AC: At Hardcomics which is the labour of love of Serbian publisher Miloš Jovanović, very passionate about comic books. He only publishes about three books a year, you can imagine the funding is very limited, and print editions are small, about 1000 copies each. By the way, when I published I had no specialist background, I’d not been to arts school or such.

AV: I’m even more jealous now. I’ve never been able to draw or paint.

AC: Well, you see what the drawings are like. Now I draw better. In any case, the book was well received, better than I expected. Naturally, it was bought primarily by Romanians, mostly people our age, but also quite a few foreigners. Maybe out of curiosity. It’s written in English. This book made me an illustrator. I ended up quitting my previous job – I was a copywriter at an Ad agency – because this book made me realise this is what I want. But I’ve suffered from impostor’s syndrome for a long time, because I had no specialist studies beforehand. I used to be embarrassed to talk about it, I was almost apologetic.

AV: I know the feeling too well! When I started with photography it was just a hobby and I had no academic training. My MA came later, in my ‘old’ age so to speak!

AC: Yes, it was a long period of acceptance, where the apologetic tendencies were ever so present. I was always saying things along the lines of ‘well, that’s all I could do’ and so on – and for what? Now I envy the person I was back then.

AV: Were you braver?

AC: Yes, I was. I’m not so brave anymore. Although I did get another book out after that, on depression – that was drawn very beautifully. But now… I keep thinking that maybe that’s all I had in me, because I’ve been struggling with my third book for almost six years. I struggle because I don’t have this courage any longer to not look at the line, at the way things are drawn, to not spend too long on the internet looking at what other illustrators produce. It’s hard.

AV: Unde ai publicat? Și unde s-a distribuit?

AC: La editura Hardcomics care este proiectul de suflet al sârbului Miloš Jovanović, foarte pasionat de bandădesenată. El publică cam trei cărți pe an. Adică, îți dai seama, fonduri foarte mici, publicații cu o mie de exemplare. Apropos, când am publicat nu aveam nici un background, n-am făcut facultate de arte.

AV: Oo, sunt și mai invidioasă acum. Eu n-am putut să desenez sau să pictez vreodată.

AC: Ee, vezi cum sunt desenele. Acum desenez mai bine. In orice caz, a fost foarte bine primită, mai bine decât mă așteptam. Au cumpărat-o mai mult, normal, români de vârsta noastră, dar au cumpărat-o și foarte mulți străini, poate din curiozitate. Si e scrisă în engleză. Pornind de la cartea asta am devenit ilustrator. M-am lăsat de ce făceam înainte, eram copywriter la o agenție de publicitate, și după ce am scos cartea asta mi-am dat seama că asta îmi doresc. Dar am avut foarte mult timp sindromul impostorului pentru ca nu studiasem înainte. Îmi era jenă să vorbesc despre ea, mă scuzam, mult timp.

AV: Cunosc sentimentul, prea bine. Și eu când am început să fotografiez era doar un hobby, nu aveam nici o pregătire academică. Și după, târziu, am făcut un masterat, acum la ‘bătrânețe’ să zic așa!

AC: Da, a fost o perioada lunga de acceptare, în care tendința asta de a te scuza a fost prezentă mereu. Să te scuzi, să zici: eee, atât am putut, si pentru ce? Dar, cumva, mă invidiez pe mine cea de atunci.

AV: Erai mai curajoasă?

AC: Da, eram. Nu mai sunt așa de curajoasă. După, am mai scos un roman grafic despre depresie, desenat foarte frumos. Dar acum… poate atât am in mine, pentru că acum mă chinui la a treia carte cred că de vreo șase ani. Mă chinui, că nu mai am curajul asta, să nu mă uit la linie, la cum e desenat, să nu mă uit pe internet să văd ce fac alții. E greu.

AV: What do you think of today’s Romania: how is the communist period perceived and talked about? Is there interest from artists to bring stories from those times to the surface? Are there still nostalgics?

AC: Yes, there are nostalgics – but it depends on where you go. In smaller towns and villages there are old people who, after the 90s, may have suffered greatly from precarity, maybe even more than the 80s. And they sadly grew old, an ugly old age. In Bucharest, maybe not so much. There have been quite a few films, there’s been a lot of discussion. But I don’t think there’s any interest anymore.

AV: Do you think there’s a saturation?

AC: I think there is a saturation but it’s unfortunately all superficial. For example, if you go to the Sighet museum, there’s a lot of information, which should be disseminated a lot, and it’s not. Politically, this wasn’t wanted at all. And then there’s the nationalist trend in recent years, and I am not sure how they relate to the communist period, whether they just misrepresent it. Most people don’t want to be associated with that, with this nationalism, or they prefer to forget or not talk. You keep hearing how ‘we have bigger problems’ or ‘it’s been a long time’.

AV: Is there a generational divide?

AC: Yes, there is. Although I know nothing about the Tik-Tok generation. I don’t have children, so I don’t know. But I think they’re not interested. It’s something to do with grandparents and parents and then… My mother says she feels sorry for our generation. Because she was a teacher, she had a job from the age of 20 until she retired, certain and stable. She had an apartment and a few holidays… But she forgot a lot, because that’s what happens, you forget. And the older she gets the more she doesn’t think it so important that we had no access to books, films, information. Because at the moment she doesn’t suffer from lack of internet or such, for example.

AV: Cum percepi tu în România, în momentul actual, cum se vorbește despre perioada comunistă? Există interes de pe partea artistică, să se aducă la suprafață poveștile de atunci? Există încă nostalgici?

AC: Da. Exista nostalgici, dar depinde unde te duci. In orașele mici, și la sate, unde oamenii mai bătrâni care, după 90 au suferit de precaritate, poate mai mare decât în anii 80. Si au îmbătrânit din păcate trist si urât. În București nu prea mai există. Adică au fost destule filme, și s-a tot vorbit. Dar cred ca nu mai e nici un interes.

AV: Crezi ca s-a ajuns la o saturație?

AC: S-a ajuns la o saturație dar din păcate e superficiala. De exemplu, dacă te duci la muzeul de la Sighet, acolo e foarte multă informație. Care ar trebui spusă, și spusă mult, și nu este. Bine, și politic nu s-a dorit absolut deloc. Și mai e și tendința asta naționalistă din ultimii ani care de fapt eu nu prea știu cum se raportează ei la perioada comunistă, dar s-ar putea să o preia așa, într-un mod mincinos și oamenii care nu vor să fie asociați cu asta, cu naționalismul ăsta, preferă să uite sau să nu vorbească. Tot auzi cum: avem probleme mai mari, au trecut deja mulți ani...

AV: E diferență între generații?

AC: Da, este. Deși despre generația Tik-Tok nu știu, sunt complet ruptă. Nu am copii si atunci nu știu... Dar nu cred ca îi interesează. E ceva legat de părinți și de bunici și atunci…Maică-mea de exemplu zice ca-i e milă de generația mea. Pentru că ea a fost profesoară, a avut un job de la 20 de ani pana când a ieșit la pensie, așa, sigur si stabil. A avut un apartament, făceam și niște vacanțe. A uitat multe, că așa se întâmplă, uiți. Și cu cât a îmbătrânit, nici nu mai consideră important că nu aveam acces la cărți, la filme, la informație. Pentru că nici acum nu suferă că nu are acces la internet de exemplu.

AV: Back then, we didn’t know any different, right?

AC: Exactly, we had no comparison. But I remember we had a solution for everything. I don’t remember suffering for not having chocolate, I’d improvise something mixing cocoa with sugar.

AV: Haha yes, in a mug. We were taught to make do. I remember one time when our grandmother was looking after us, it was a very difficult period, and she made us Scovergi (EN a type of flatbread). I remember her being sad, and I didn’t understand why, because I liked her scovergi.

AC: Yes, they’re very good!

AV: But thinking back now, as an adult, I know that the poor woman had nothing else to feed us.

AC: Yes, just some flour and water

AV: A little oil …Yes, I think that even if we were children back then we carry our mothers’ and grandmothers’ trauma.

AC: Yes, I think so too, unfortunately.

AV: And for me it’s important to tell these stories, not just for us, but also for them.

AV: Pe atunci nu știam altceva.

AC: Exact, nu aveam comparație. Dar țin minte că aveam soluții pentru orice, adică nu sufeream ca n-am o ciocolată, că făceam ceva o chestie cu cacao si zahăr.

AV: Haha da, într-o ceașcă. Eram învățați sa improvizam, să ne descurcăm. Eu țin minte că o data când stătea bunica cu noi, și era o perioada cruntă, într-o zi ne-a făcut scovergi, si țin minte că părea trista. Și eu nu înțelegeam de ce, că mie îmi plăceau scovergile făcute de ea.

AC: Da, sunt foarte bune!

AV: Dar mă gândesc acum ca adult, că biata femeie nu avea altceva sa ne dea de mâncare.

AC: Pai, da, un pic de făină, apă

AV: Un pic de ulei…Da, eu cred ca noi chiar daca eram copii atunci, purtăm trauma mamelor si bunicilor.

AC: Da, și eu cred asta, din păcate.

AV: Si pentru mine e important sa spunem poveștile astea, nu doar pentru noi, dar si pentru ele.

AC: Yes, honestly, I’d love to be able to tell a story from mum’s point of view. They, as a generation, never had the exercise of introspection, and they cannot express themselves because of that – they don’t have a dictionary, a lexicon of feelings. For example, I wanted to ask her about my dad, who died of cancer when I was seven. I know nothing about their relationship, as a couple, for example, and that could maybe help me understand more about me in a couple. She can’t, or won’t, tell me, either she said she doesn’t remember or doesn’t know how to describe how my dad was as a husband, how they were as a couple, beyond the anecdotal stories that I’d heard hundreds of times.

AV: A generational issue? A cultural issue? It was the same in my family – nobody ever spoke of couple of family problems, of relationships. And I think we all grew up with this handicap that we don’t know what’s normal, what to aspire to.

AC: It’s true; many in our generation in Romania have no benchmarks.

AV: And many in our generation have no children. My sister and I included.

AC: Yes, and if they do have children, I noticed they practically re-educate themselves. Neither my brother nor I have children either. We said the thread of trauma stops with us. My poor mother had a difficult family history – with grandad being a political prisoner at Pitesti. Two years. And then forced labour at the Canal.

AV: Horrendous!

AC: Yes, so my mum had a difficult childhood from this point of view, and I think that’s when this habit of not talking started to build. And it just grew as tabu. My grandmother, for example, had to divorce grandad when he was in prison so she could continue to work. To keep her job as a primary school teacher – that’s what they both did. I got his Securitate file, you know that you can do that now – and there were lots of people informing on him because he got drunk at the pub and talked badly of communists. He kept saying they’re all stupid and the Americans will come, he talked badly of anyone who was a communist party member. It’s not that he had wealth or anything – but he got convicted for being an enemy of the people.

AV: Just for talking against the system.

AC: Yes, can you imagine. I kept reading and thinking, thank goodness we live in our days.

AV: But you see, this also contributes to inter-generational trauma. Imposed silence – I remember when I grew up there was an obsession with not speaking, not saying anything at all, not even pronouncing Ceausescu’s name.

AC: Da, sincer mi-ar plăcea să pot să spun o poveste, din perspectiva mamei. Ele, ca generație, nu au avut exercițiul introspecției, deloc, si din cauza asta nu pot exprima, nu au un dicționar al sentimentelor, un lexicon. De exemplu, as vrea să o întreb despre tata, care a murit de cancer când aveam șapte ani. Nu știu nimic despre relația lor ca un cuplu, de exemplu, și asta poate m-ar ajuta să înțeleg mai mult despre mine într-un cuplu. Nu poate să-mi spună, sau poate nu vrea, sau nu-și mai amintește, sau nu știe să exprime cum era tatăl meu ca soțsau cum erau ei împreună, dincolo de aceleași anecdote pe care le-am auzit de o suta de ori.

AV: O problemă de generație, de cultura? La fel și la noi în familie. Nu se vorbea niciodată de problemele de cuplu sau de probleme din familie, de relații. Și într-un fel am crescut cu handicapul ăsta, că nu știam ce e normal, la ce să aspiri.

AC: Așa e, mulți din generația noastră, din România, nu au repere.

AV: Și mulți din generația noastră nu au copii. Nici eu nici sora mea nu avem copii.

AC: Da, și dacă au copii, am observat că practic se re-educă ei. Da nici fratele meu nici eu nu avem copii. Am zis că la noi se oprește șirul de traume. Mama mea săraca, cu istoria ei de familie – bunicul a fost prizonier politic la Pitești. Doi ani. Si după aia la Canal.

AV: Cumplit!

AC: Da. Deci mama a avut o copilărie destul de grea din punctul asta de vedere, și cred că de atunci a rămas cu obiceiul ăsta de a nu vorbi. Si acest tabu s-a extins.

Bunica mea, de exemplu, a trebuit să divorțeze de bunicul cât a fost el în închisoare, ca să poată să lucreze. Să fie învățătoare în continuare - erau învățători amândoi. I-am luat dosarul, știi că poți să iei dosarele, și am citit tot și erau foarte multe denunțuri pentru că era beat la cârciumă si zicea că toți comuniștii sunt proști și că o să vinăamericanii, vorbea foarte urât de toți din jur care erau în partidul comunist. Nu era din cauză că avea avere sau ceva, dar a fost condamnat ca dușman al poporului.

AV: Deci numai pentru că vorbea împotriva sistemului.

AC: Da, iți dai seama. Când am citit m-am gândit, doamne ce bine ca trăim acum.

AV: Dar vezi și asta contribuie la trauma inter-generațională. Tăcerea impusă, țin minte și eu când am crescut, era o obsesie să nu vorbești, să nu spui nimic, nici măcar să nu-i spui numele lui Ceaușescu.

Let’s talk about future plans. Do you think you’ll approach this period of time again? To create something based on your family’s stories? I wonder if you might be interested in telling your grandfather’s story somehow.

AC: I don’t know, I wouldn’t want to feel like I’m trivialising it. I don’t have the resources, or an academic approach. Plus, my grandmother is no longer alive. My mother doesn’t want to talk, and she was a child back then anyway. It wouldn’t be autobiographic, but rather fictionalised to some degree. I’d rather focus on something closer, like the relationship with my mother and how I became the woman I am today. Because – I don’t know how you feel, having lived for a long time in England as an adult – but I feel like I’m in between two worlds. You know, one that’s very forward, very Westernised, and one that’s so retrograde – well, simplifying quite a lot of course. I’d like to do something about that. But you need a great deal of honesty, which is difficult when you write. With drawing, it’s easier, but you have to start from something written. And it’s very hard to not lie to yourself, and not lie in general. To not try to be liked. And on the other hand, I’m thinking, who cares?

AV: Someone very close to me asked me that when I started this project.

AC: Well if you do a PhD at least your supervisor cares, or at least you have a structures, some steps to follow, but I do ask myself every day, who cares?

AV: As you said, I also feel between two worlds – and I don’t think there are that many people in the category of people who do care. But I’m determined because I think that after our generation – maybe in just 20-30 years’ time – there won’t be anyone left with lived experience and memories and all these stories will disappear.

AC: I think about that too, it’s true. Just like others got lost. And this is the most important thing, that they don’t disappear.

Să revenim la planuri pentru viitor. Crezi că vei mai aborda perioada asta? Să faci ceva pe bază de familie? Mă gândesc că ar fi interesant poate să spui și povestea bunicului cumva.

AC: Nu știu, mi se pare că nu vreau să o trivializez. Nu am resursele, nu am o abordare academică. Plus, bunica mea nu mai trăiește. Maică-mea nu vrea să zică, și de altfel si ea era mică atunci. Deci nici măcar n-ar fi autobiografică. Ar fi o poveste ficționalizată cumva. Mai degrabă, ceva mai aproape, aș face ceva despre relația mea cu maică-mea și cum am devenit eu o femeia care sunt acum. Pentru că - nu știu cum te simți tu, care ai trăit mult ca adult în Anglia – dar eu mă simt că trăiesc între două lumi. Știi, o lume de-asta super vestică, forward și o lume retrogradă, bine simplificând mult. Da, mi-ar plăcea să fac ceva despre asta. Dar trebuie o foarte mare onestitate, care e grea când scrii. Cu desenatul e ușor dar trebuie sa începi de la ceva scris. Si e foarte greu sa nu te minți pe tine, si sa nu minți. Adică sa nu încerci să placi. Da, asta pe de o parte, și pe de altă parte, cui îi pasă?

AV: Asta m-a întrebat si pe mine cineva apropiat când am început proiectul.

AC: Da, că dacă faci un doctorat, îi pasă profesorului, adică ai niște structuri, pași de urmat, dar eu aproape în fiecare zi mă întreb, cui îi pasă?

AV: Cum ai zis și tu, mă simt între doua lumi și constat că în categoria celor cărora le pasă nu e multă lume. Dar sunt determinată, pentru că mă gândesc că după generația noastră – mai avem poate 20-30 de ani – nu va mai exista nimeni cu experiență trăită și toate povestirile astea o sa dispară.

AC: La asta mă gândesc și eu, așa e. Cum au dispărut altele. Asta e cel mai important, să nu dispară.

You can find more of Andreea Chirică’s recent work on Instagram