Rest in peace, Paraschiva

Today marks exactly 80 years from the bombardment of Bucharest by the Anglo-American air forces during the second world war. 4th April 1944.

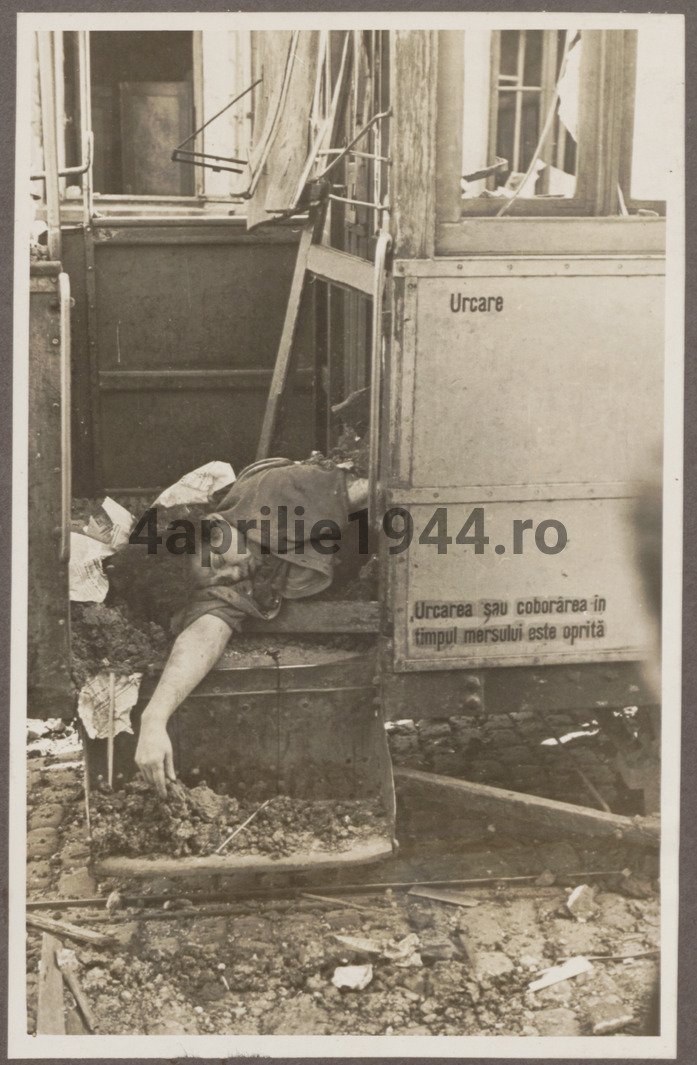

I have only recently found out that my maternal great-grandmother died on this day, burned alive in one of the train carriages at Gara de Nord (Bucharest’s main train station), one of the most heavily bombed areas.

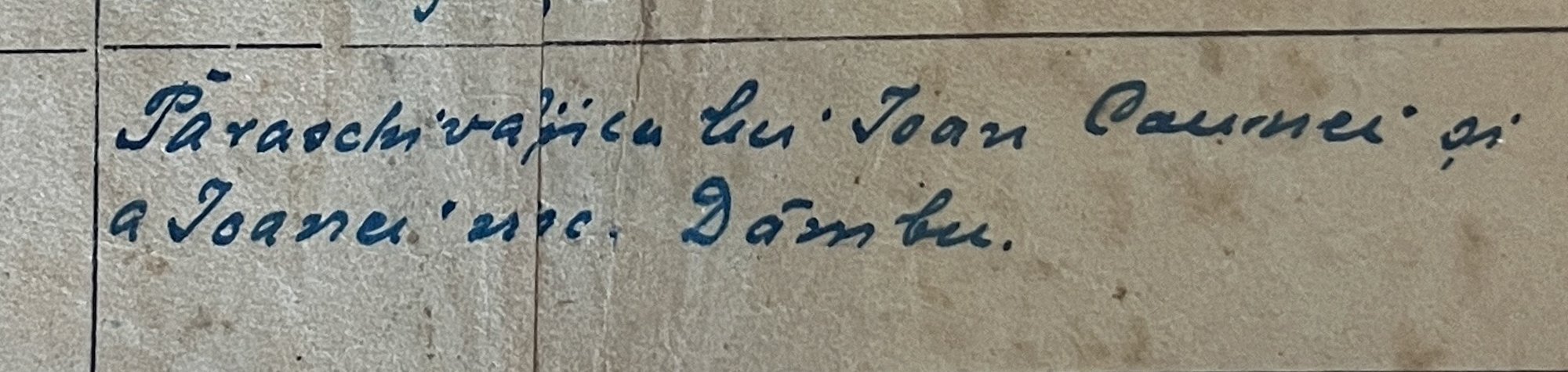

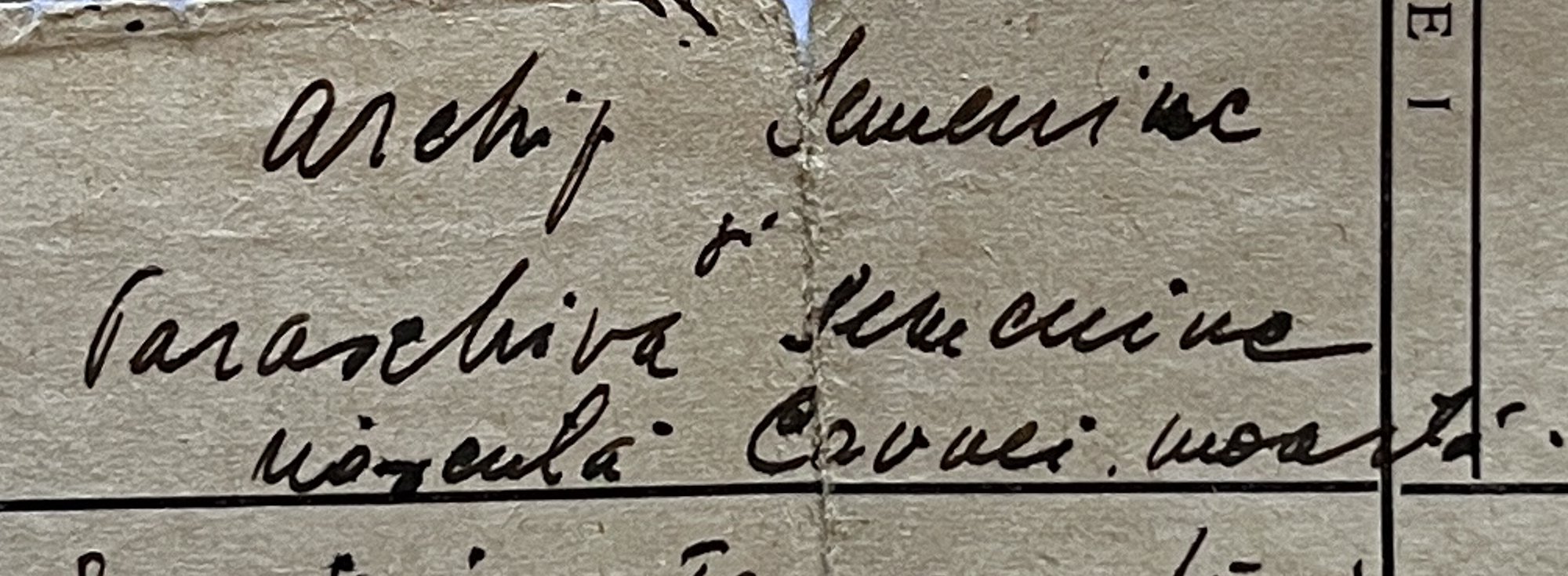

I don’t have a photograph of her. All I know, all I have, is her name, as recorded on my grandmother Maria’s birth certificate from 1921, and then her name again on Maria’s marriage certificate from February 1945, when she is recorded as deceased.

Paraschiva was from Iaslovat, a town in the region of Bucovina, in the north of Romania. Since the first world war, this region suffered greatly from the advancement of the Russian Red Army, which ended up in the annexation of North Bucovina, a territory that has since been part of the USSR and then Ukraine.

Romania’s alignment as an Axis country at the beginning of WW2 was in part to stop the Russian invasion and the relentless and violent attempted campaign of russification of the area, culminating in the annexation of Basarabia (now the republic of Moldova) and north Bucovina. But this is not a political history lesson. It is context for my family history.

Paraschiva’s family was, at the time, running away from the war front which was advancing well into the north of the country and her former home, as were thousands of others seeking refuge from Basarabia, Bucovina and Herta.

An ‘allies’ campaign of heavy bombardments started in April 1944, in which thousands of civilians were killed, my great-grandmother Paraschiva amongst them. Assumingly, the attacks were meant to target and cut off the petrol supply to the Germans, but thousands of civilians and refuges were killed in the process, having nowhere to go and take refuge when the alarms sounded.

The attacks continued relentlessly until Romania eventually switches sides in August 1944, sealing its fate as a satellite of the USSR for the next 45 years.

Paraschiva ran away from the Russians to be killed by the Americans. She was a simple woman from the countryside, caught in the crossfire of a war in which Romania’s strategic geographical position and natural resources made it a valuable asset exploited by the big powers, facilitated by its own morally dubious politicians no less.

Over 5000 civilians died in the bombardment, on the day or in the aftermath, due to their injuries. Their bodies, it would appear, lie in a communal, unmarked grave. For many years we never learned about this event, not even after 1990, and to this day there is hardly any reference to it.

Image credit: https://4aprilie1944.ro

Caption reads: Communal grave where the 2,942 Romanians killed during the bombardment of the 4th April as well as people killed in subsequent raids were buried, totalling 5,524 dead. It was first named the ‘4th April Cemetery’. Now there is no indication of it, and it is just an empty field.

I don’t recall anybody in my family speaking about this, but then they never did speak of war times, possibly too painful to remember. It’s also possible that if this was ever mentioned, I was too young to remember. Now there is nobody with living memory of those times left to ask.

Recently, as I started to become interested in my family genealogy, it did come up in a conversation with my second cousin whose mother (Paraschiva’s oldest daughter) told her that she was there at the time, already on the platform and able to take refuge with other family members, while Paraschiva was trapped in the burning train carriage. Witnesses to this awful family tragedy and forever carrying this immense trauma within them.

Wars are instigated and led by politicians, army generals and arms dealers. History is written by the victors – again, politicians – to suit the narrative that shapes the post-war evolution of a region. But personal, family, human history too often remains unwritten and disappears alongside the carriers of its living memory. Trauma remains embodied across generations, the post-memory of tragedy lingering, unknown and unspoken of for years, until it somehow makes its way to the surface in bursts of unexplained sadness, anxiety, depression. It is this history that we need to write and keep alive, reclaiming our past, restoring it into collective memory.